Background information

19 predictions for gaming in 2026

by Philipp Rüegg

87 per cent of all retro games are no longer legally playable today. How did it come to this – and what does it mean for your favourite game?

It’s December 1994. On the radio, grunge gives way to the big Britpop wave, every shared flat has at least one Pulp Fiction poster on the wall and a 30-year-old Jeff Bezos launches his online bookshop from a garage in Washington. Back then with more hair and fewer ambitions of world domination.

1994 was also a formative year for the video game industry, as the very first PlayStation was released in Japan – also in December. Almost simultaneously, Snatcher was released, a rather obscure adventure game for the equally obscure Sega CD console. Snatcher is a point’n’click game in a sci-fi setting that takes heavy inspiration from Ridley Scott’s cult film Blade Runner. The game would probably be largely forgotten today if the man in the director’s chair hadn’t been Hideo Kojima. Alongside Shigeru Miyamoto, the Metal Gear creator is probably the best-known video game director. If you want to know more, there’s a brief introduction to him here.

Unsurprisingly, his fans want to play his older works in the future, but this isn’t easy.

Let’s assume emulation (more on this below) isn’t your thing and you want to play Snatcher legally. You’ll need:

the game, which is rarely traded on eBay for under 1,000 francs/euros, a Sega CD console for around 250 francs/euros and a tube TV for another 150 to 200 francs/euros to connect it. There are other options for the latter, but hey: you want the maximum authentic experience, don’t you?

So, the whole thing will set you back at least 1,400 francs/euros. Is it worth it? Probably not. Snatcher is a cool game, but for 1400 francs/euros you could have the entire console generation in your living room, which offers more in the long term.

Admittedly, it’s a fringe case. You can also get hold of other retro games and consoles for less money. However, Snatcher illustrates a precarious problem: a huge part of video game history is difficult to access today and in some cases has even disappeared completely.

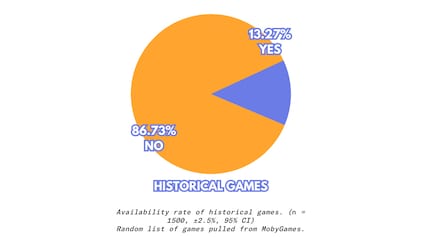

The Video Game History Foundation is a non-profit organisation in the US. Founded in 2017 by Frank Cifaldi, its aim was to preserve gaming history. In 2023, the association published a study which revealed that 87 per cent of all games released in the US market before 2010 were inadequately archived.

87 per cent – a figure that sounds less like a statistical survey than an alarm signal for cultural history.

The reasons for this are numerous and reflect the dysfunctionality of an industry that likes to talk about its cultural heritage, but at the same time does too little to actually preserve it.

To be fair, I need to point out that the starting position isn’t entirely straightforward. The biggest challenge is licensing chaos. When studios or publishers go bankrupt, the rights to their games often disappear into an opaque web of creditors and legal successors, making a new release practically impossible.

Some games also use licensed music, brand names or film rights. The distribution rights usually expire after a few years, then the title can’t be sold. A current example is F1 23, which was removed from digital stores in spring. The racing game wasn’t even two years old at the time.

Technical incompatibility is another killer. Games were developed for specific hardware that no longer exists today. Without complex emulation or porting, they’re unplayable on modern systems. Most developers shy away from the cost of reprocessing.

In recent years, always-online has also become an increasing problem. Many modern games require a server connection, even for single-player. If servers are shut down, the game’s dead – regardless of whether it was bought legally or not.

Finally, there’s a lack of systematic archiving. Unlike films or books, there aren’t any established institutions that consistently collect and preserve video games. Source codes get lost, developer documentation disappears and with it the possibility of preserving games for future generations.

The complexity of the problem can also be seen in the approach developers and publishers take. Let me show you what I mean:

A few years ago, then PlayStation boss Jim Ryan allowed himself to be carried away with the flippant statement that nobody wants to play old games. Today, the Sony Group is endeavouring to have at least some of its legacy titles available. You can find various retro games in the PSN store, such as The Legend of Dragoon, Dark Cloud and Twisted Metal.

As always, Nintendo goes its own way: its online membership offers classic games, but the selection looks as if an intern had thrown darts at a list blindfolded. The Wii Shop Channel was more progressive in 2006 – and that’s saying something.

Ubisoft, on the other hand, seems to be continuing its efforts to establish itself as the most customer-hostile publisher of all. In January 2024, the French company let it be known that players «will need to get comfortable with not owning the games they buy».

A few weeks later, the developer shut down the servers of racing game The Crew, making the game completely unplayable – even in single-player mode. A digital middle finger to all those who paid 70 francs/euros for the title. After massive protests, Ubisoft announced that its sequels The Crew 2 and The Crew Motorfest will remain playable offline even after a possible server shutdown.

Let’s start with the good news: the situation has improved recently. This Ubisoft example shows that the issue is at least being taken more seriously than it was a few years ago. Distribution platform GOG.com is also doing important pioneering work in the PC gaming sector.

For almost 20 years, this subsidiary of The Witcher developer CD Projekt has been fighting to preserve retro games and keep them available. The company employs more than 780 people, including numerous legal experts, who find out in intricate processes which doors to knock on to bring almost forgotten games out of obscurity.

In addition, many non-profit companies such as the Video Game History Foundation and numerous private individuals are also committed to the cause. The most prominent example of the latter is currently the Stop Killing Games initiative by YouTuber Ross Scott. Fellow editor Pape dedicated a longer article to the project in June, so I’m just included the key information here. In brief, Stop Killing Games aims to ensure that video games you buy remain playable even after server shutdowns, if necessary through mandatory offline modes or community servers. Essentially, anyone who buys a game should be able to play it forever, not just as long as it suits the publisher.

The approach is good, but by no means addresses all sides of the problem.

If you don’t want to spend a fortune on retro stuff and don’t fancy waiting for your favourite game to be given an official re-release at some point in the distant future, the only option is emulation. This makes it possible to play old video games on modern devices by using software that imitates the original hardware (such as NES or PlayStation). The process itself is legal, but it gets more complicated when it comes to downloading software. My colleague Rüegg spoke at length about this with Swiss legal expert Martin Steiger.

You can certainly argue that it’s only fair to help yourself when publishers obviously don’t want to make any money. But you have to decide for yourself using your own moral compass.

Minecraft inventor Marcus Notch Persson also recently joined the discussion and commented: «If buying a game is not a purchase, then pirating them is not theft.»

The statement doesn’t completely miss the truth, but it’s very reductive. Among other things, Marcus ignores the fact that nowadays we rarely actually buy games – just the licence to use them. On Steam, this clause has been firmly anchored in the terms and conditions for several months and is part of the purchase agreement between you and the platform.

Scott’s Stop Killing Games initiative has collected over 1.4 million signatures and was submitted to EU governments and legislators on 31 July. The petition has a good chance of being accepted – it’s presumably an «easy win» for decision-makers. Consumer protection is a good sell and gaming is a popular topic that attracts potential voters who are otherwise only interested in politics to a limited extent.

If the EU introduces new consumer protection laws for games, Switzerland would probably adopt them sooner or later – after all, our country has already committed to adopting relevant EU legislation in over 100 bilateral agreements. Similar to the standardised USB-C charging cable that Apple has had to use here since autumn 2024.

With a bit of luck, this undertaking will also sensitise the gaming industry to the need to further preserve its history. At the moment, this is still wishful thinking.

Unfortunately, an all-encompassing solution is currently not in sight, and a quick look at the Delisted Games website shows that titles continue to disappear from the market. Some of them forever. If you want to make sure you can still play your favourite game in ten years’ time, the only option at the moment is to buy a physical data carrier.

But perhaps this is also the ultimate meta level: games teach us that nothing lasts forever – not even themselves.

In the early 90s, my older brother gave me his NES with The Legend of Zelda on it. It was the start of an obsession that continues to this day.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all