Background information

The new Swiss data protection law – what you need to know

by Florian Bodoky

The federal government’s wallet app is called Swiyu – it’s where your E-ID will be stored. In this article, I’ll go into exactly how the E-ID and app work as well as any downsides.

On 28 September a referendum will be held on the E-ID – more precisely, on the Federal Act on Electronic Identification Services (e-ID Act).

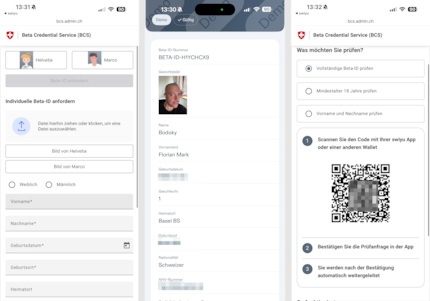

A few weeks ago, the federal government promoted its associated wallet app Swiyu to the next phase, namely a so-called public beta. If you’d like, you can download the app for Android and iOS and try it out for yourself. Mind you, it’s just a dry run, you can’t actually use it like a real ID yet. This will only kick in starting autumn 2026 at the earliest, assuming the referendum passes.

Swiyu is the wallet app itself. In other words, the digital home in which you store your E-ID if you want one. The somewhat strange name is a combination of Switzerland and you. It’s meant to give off a «From Switzerland, for Swiss people» vibe.

You can apply for an E-ID via the Swiyu app. If you do this, the federal government will first check your identity. For this, you’ll have to scan your ID and take a selfie with a so-called liveness check. Liveness basically means the software recognises whether it’s really a living face and not a photo or video. Presentation Attack Detection (PAD) is used for this purpose.

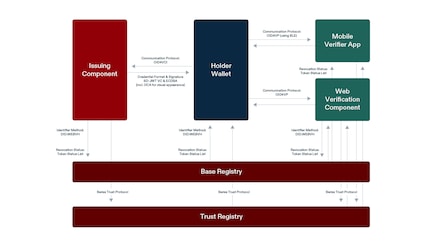

Once you’ve completed the check, your smartphone will produce a pair of device keys in the wallet. First, this duo consists of a private key that’s generated and stored in your smartphone, in a location that’s completely decoupled from the main processor. On the iPhone, this area is called Secure Enclave, on Android phones it’s Trusted Execution Environment. Second, there’s a public key. That one will be passed on to the federal government, who issues your E-ID.

The state then issues a verifiable credential (VC). VC is a data package that contains facts about you, similar to a classic ID: your name, when you were born, your hometown and so on. This credential is signed by the government using the so-called ES256 signature. It’s a third, state-owned key. So, the federal government effectively signs your E-ID as the issuer.

Now the public key from before comes into play. It’s also entered into the credential for so-called device binding. This means that your E-ID isn’t just a document free to be copied, but firmly linked to your mobile phone and your private key. Both the VC and your private key are now stored locally on your device. You have your very own E-ID.

The anti-referendum committee has criticised the fact that biometric data such as selfies or video recordings are taken and processed when issuing the E-ID. They warn that such sensitive data represents a major risk since it’s stored for a long time and could be misused in the event of a hack. In addition, they claim that the procedure using selfie checks, liveness detection and PAD isn’t one hundred per cent secure against attempts at deception such as deepfakes.

Proponents counter that the PAD procedure was developed precisely for this purpose and reliably detects deception and that verification is carried out in accordance with international standards.

Your E-ID will be stored directly in the wallet app on your smartphone. The exact technical name for the E-ID is Selective Disclosure JSON Web Token Verifiable Credential. In plain English, that’s a digitally signed and verifiable data package in JSON format that can selectively disclose information. You can think of the wallet app as a vault, while SE and TEE are a secure bunker. Your E-ID will be stored in a stable safe, which in turn is located in a bunker. The proper owner is needed to unlock the bunker and open the safe: you protect it in the traditional way via a PIN, fingerprint or Face ID.

There’s also device binding: your E-ID is bound to your phone with the private key. It’s why, for example, a screenshot of your E-ID won’t work. Anyone checking will realise that although there’s a picture of your E-ID, it’s no longer in the safe and bunker – and would be rejected. This is why you need to reissue your E-ID when you change devices, since the credential is permanently linked to the key on your old mobile phone. It’ll also require another liveness check with PAD. You can neither copy your old E-ID nor transfer it to your new device using a smartphone transfer app – it would no longer work.

Last but not least, your E-ID data can’t be changed either. You can’t make yourself older, for example. This is ensured by the government signature (ES256). Otherwise, it’d quickly become apparent that your ID isn’t state approved.

One major point of criticism concerns the lengthy storage of biometric data. According to the «No» committee, selfies and identification videos being stored for up to 15 years is highly problematic. Since it’s all sensitive and unalterable data, there’s a considerable risk.

Supporters point out that the long storage period is necessary so that the federal government can carry out a review in the event of a dispute or allegations of misuse. In addition, access control is always carried out under state supervision as well as managed and protected under Swiss data protection law.

If you want to use the E-ID in a bar or supermarket, to confirm your age for example, here’s how you’d do it. First, the bar has a verification service, for example an app. This starts a request using the OpenID for Verifiable Presentations (OID4VP) protocol, to test your age, let’s say. This request contains a so-called presentation definition, a list with all the data that the verifier wants from you. In this case, information regarding your age and whether you’re allowed to drink. This request is packed into a URL and displayed as a QR code. You can scan it with the QR reader in your Swiyu app.

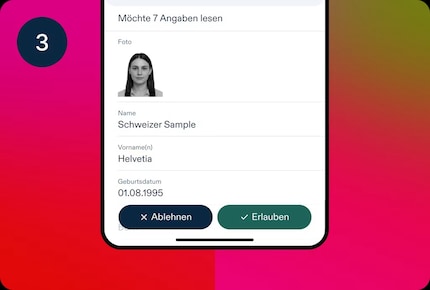

Your wallet then checks who the other person is. To do this, it verifies their DID (digital identity anchor, which uniquely identifies a company or organisation). This also checks whether they’re allowed to receive this information. It also verifies which attributes are in the presentation definition. You’ll then receive a message in the Swiyu app, for example «The Türmli Bar in Winterthur would like to know if you’re already 18.» Just tap on «Agree».

The wallet then creates a verifiable presentation (VP). This data package contains the information that you’re at least 18 years old. There’s also the state key, which proves that your credential was genuinely issued by the federal government. And finally, your device signature (device binding) with your private key, which proves that the verifiable presentation really came from your smartphone. In addition, a unique random number called a nonce is built in. It prevents someone from simply reusing the presentation later.

The verifier then checks the signature (does the information come from the federal government?), the status (is the E-ID still valid?) and the issuer (is the federal government allowed to issue E-IDs at all?). But the bar sees none of this. It only receives the information: yes, you’re at least 18. Even who you are or your exact date of birth remain secret. This way, the bar gets the information it needs and you don’t have to reveal anything that isn’t necessary.

The «No» committee has warned that the E-ID could become a surveillance tool for everyday life. Anyone who uses it regularly will leave behind data traces that could theoretically be used to create profiles – for targeted advertising or political influence, for example.

Proponents point to the principle of data minimisation. With the E-ID, only a necessary attribute needs to be disclosed. Only «over 18» instead of a date of birth or full name, for example. Each query is visible to the user and only released with the user’s consent. In addition, every info transaction is visible in the wallet on the device. You can check at any time when you sent what information to whom.

I've been tinkering with digital networks ever since I found out how to activate both telephone channels on the ISDN card for greater bandwidth. As for the analogue variety, I've been doing that since I learned to talk. Though Winterthur is my adoptive home city, my heart still bleeds red and blue.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all