When will humans become cyborgs?

Cyborgs are no longer just the product of science fiction: pacemakers turn people into cybernetic beings. The understanding of where being a cyborg begins and where being human ends has changed over time. Are computers, wearables, smartphones and the like already turning us into cyborgs?

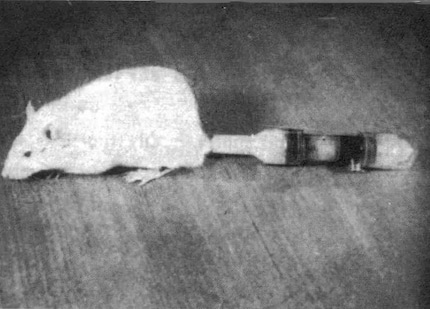

Cyborg is short for "Cybernetic Organism". The term organism contained in Cyborg opens up the meaning of cyborg. It does not necessarily have to be a human/machine. Animals or plants can also be cyborgs. The term was first used in 1960 in a scientific article in the journal "Astronautics". In this article, the authors investigated how the astronaut's body could be technically extended to adapt to the conditions in space. The idea behind it: It would be more logical to modify the human body for survival in space instead of adapting the conditions in space to those on Earth. They demonstrated this using the example of a rat. An osmosis pump was implanted in the rat, which constantly supplied it with various chemicals without the rat having to do anything. According to the researchers, this rat was one of the first cyborgs. Even in this original use of the term, a cyborg is a hybrid of the organic, supplemented by self-regulating extensions.

Source: Cyborgs and space

Cyborgs vs. androids

A distinction must be made here between cyborgs and androids. Androids are a special form of humanoid robot. The best popular cultural example of this is the "Terminator" film series. Terminators are often referred to as cyborgs, but due to the lack of an organic component, they can be categorised as androids. However, the distinction is not always so simple. To illustrate this, the character Motoko Kusanagi from the manga/anime "Ghost in the Shell" is a good example. Kusanagi has had a completely artificial body since her early childhood. She was therefore organic at the beginning of her life. However, her consciousness, her personality, was transferred into an artificial body. The classic definition of a cyborg therefore does not apply to her. But it would also be wrong to describe her as an android. Personally, I would call her a cyborg because she was originally organic. Incidentally, the manga/anime is still highly topical today and still worth reading/watching (which was probably also the reason for the disastrous Hollywood adaptation in 2017).

Revival of the cyborgs

Cyborgs and androids played a role primarily in science fiction literature and films after the original use of the terms. Until the science historian Donna Haraway published her Cyborg Manifesto in 1985 (in the original: A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century) in 1985. In it, Haraway argues in favour of blurring traditional hierarchical boundaries. For example, between nature and culture/technology or humans and animals. According to her, (bio)technical developments are creating hybrid beings that cannot be categorised as belonging to one side or the other. She even says that we all turned into cyborgs in the late 20th century. She saw this as an opportunity to free ourselves from old social categorisations: Traditional opposites such as mind/body or man/woman are becoming increasingly blurred. When people are hybrid beings, the boundaries between apparent pairs of opposites are blurred. This also dissolves hierarchical differences between these pairs: The mind can no longer rule over the body, man over woman or man over machine. Haraway's text had a major influence on feminist debates in particular, but her concept of the cyborg was also used in sociology, film and literary analysis, etc. Her understanding of the cyborg is more of a discursive one. However, it opens up the term further and enables a discussion about cyborgs outside of the human/machine dichotomy.

Source: Innocence

Thanks to Haraway's opening up of the term, the transformation of hybrid beings is not only taking place on the human/machine level. The neologism cyborg, made up of "cybernetic" and "organic", already hints at another form of hybrid being. The transformation into a cyborg also takes place at the organic/digital level. The hybridisation of human/machine goes hand in hand with the hybridisation of organic/digital. On the human/machine side, cyborgs consist of human bodies linked to smart little helpers. On the other hand, they consist of their various digital avatars, through which they communicate online. This is where cyborg activism, a newer form of digital political engagement, comes in. I will discuss exactly what this is all about in a later article.

Cyborgs everywhere you look

Since the Cyborg Manifesto, our world has undergone massive social and technological change. Cyborgs in the sense of human/machine hybrids are the order of the day. Obvious examples can be found in medicine. Prostheses replace at least some missing limbs, cochlear implants take over the function of damaged parts of the inner ear and pacemakers stimulate the heart muscle to contract. Cyborg artist Neil Harbisson implanted himself with a device that enables him to perceive colours using acoustic signals. He is the first person to be indirectly recognised as a cyborg by a government (United Kingdom): He had to fight for a long time to be allowed to show his antenna on his passport photo. He achieved this by arguing that the antenna was part of his body. However, there are also people who extend their bodies cybernetically without wanting to iron out a physical disadvantage. For example, people have RFID chips implanted in their bodies. The possibilities for optimising the body seem limitless. I will discuss the potential social consequences of this in another article.

Source: Wikipadia

Are we all cyborgs?

The question arises as to how close to or how far inside the body cybernetic extensions need to be in order to turn people into cyborgs. Data glasses and other wearables extend our bodies through networked technology, at least temporarily. The same applies to smartphones, computers and all kinds of other technological objects. They are increasingly permeating our social lives and we are merging more and more with these devices. Are we already cyborgs due to our smartphone use?

The German philosopher Dierk Spreen draws the line here. He says that people only become human cyborgs when the skin barrier is crossed. Going under the skin is therefore a prerequisite for becoming a cyborg. This seems to make sense. Depending on how broadly cybernetic extensions are defined, people who wear glasses, for example, can already be regarded as cyborgs. If you take the whole thing to the extreme, every object used by humans can be regarded as a technological object. This means that we humans have always been cyborgs, at least some of the time. The cyborg/non-cyborg distinction would therefore be obsolete. Spreen therefore develops the slider model. This involves moving a slider on a scale between a low-tech and a high-tech body. If the slider on this scale exceeds the skin limit, a person becomes a human cyborg. Spreen cites the implantation of RFID chips as an example: If a chip is implanted, the slider crosses the skin boundary. The person then becomes a human cyborg. If the chip is removed again, the slider moves back to the other side of the boundary. He assumes that the degree of mechanisation and cyborgisation increases with increasing age and progress in technological development. Spreen considers the systematic development of body-invasive cybernetic technologies to be a cultural innovation. This can be traced back to advances in the newer life sciences and computer technology. This is also his argument against the statement that humans have always been cyborgs.

Although Spreen's slider model makes sense, I would not make the boundary to becoming a cyborg dependent on going under the skin. This view seems too narrow to me. Computers, smartphones and wearables are changing our lives more than other technological objects to date. They are also opening up the digital sphere. Our lives no longer take place only in the organic realm, but also in the digital realm. In addition to becoming cyborgs at the human/machine level, people can also become cyborgs at the organic/digital level. We do not constantly operate computers, smartphones and wearables as if we had them implanted. However, our actions are transferred to the digital realm through their use and exist there parallel to the organic. I would therefore answer the question of whether we are all cyborgs with yes, but not at all times.

How do you see it? Are we all already cyborgs or are we still a long way off?

From big data to big brother, Cyborgs to Sci-Fi. All aspects of technology and society fascinate me.

From the latest iPhone to the return of 80s fashion. The editorial team will help you make sense of it all.

Show all