The world of cyborgs: a society of equals or unequals?

We are all (at least temporarily) cyborgs. This was my conclusion in the article "When will humans become cyborgs?" The possibilities for optimising the body seem limitless. Cyborgisation will permanently change our society. In the following article, I examine the direction it could take.

It sounded a bit like someone was running damn fast in high heels when Oscar Pistorius rushed around the tartan track. The "Blade Runner", as he was also known, ran impressive times as a bilateral amputee. To make my argument clearer, I refer to Pistorius as a cyborg. Due to the technologically sophisticated lower leg prostheses made of carbon fibre-reinforced plastic, this is fine by me (you can find my definition of cyborg below). The example of Pistorius illustrates the social challenges that cyborgisation can present us with. In the following, cyborgisation refers to the development towards a human-machine society. The South African Pistorius has recently made a name for himself with the murder of his girlfriend. It is almost forgotten that he was the first athlete to take part in the 2012 Summer Olympics with a bilateral amputee. The fact that Pistorius was able to take part in the Olympics as a person with a disability suggests that cyborgisation can bridge differences between humans and cyborgs. But the whole thing is not that simple. The question was raised as to what extent the prostheses give Pistorius an advantage over people without disabilities. Couldn't people without disabilities run faster than him with appropriate prostheses? If so, they would be a form of doping and would probably have to be banned from competition.

What is a cyborg?

Cyborg is short for "cybernetic organism", a hybrid of human and machine. However, a cyborg is characterised not only by the blending of human and machine, but also by the blending of organic and digital. This is why, as I argued in the previous article, smartphones can already turn us into cyborgs, at least temporarily.

Who can afford it?

The example shows that cyborgisation can reduce differences between humans/cyborgs. By optimising his body, Pistorius has made up for a disadvantage. However, the optimisation can go so far that the disadvantage turns into an advantage. This is the crux of the matter when it comes to the fears surrounding cyborgisation: those who optimise their bodies more have an advantage over others and this has enormous social consequences.

The sports example can be applied to all areas of social life. Let's take smartphones as an example, which, as I argued in the previous text, turn us into cyborgs, at least temporarily. These are forbidden in exams because using them would give us an advantage over others. They are part of our social life and, unlike Pistorius' prostheses, they are available to anyone with the necessary change. Which brings us to the point: money. As we all know, money can't buy everything, but it can buy a hell of a lot. If you have a more expensive smartphone, you can access information faster, store more information and take better pictures. We have more advantages with a better smartphone than with a worse one. Cyborgisation therefore not only divides us humans into those who can afford an advantage and those who cannot. It also divides us into those who can afford better or less good advantages. Future technologies could have an even greater impact.

The science fiction series "Altered Carbon" provides a better illustration. In this series, people's consciousness can be digitised in so-called stacks and inserted into new bodies, in the series "Sleeves". Rich people can thus virtually afford immortality in their own bodies by cloning their own bodies and transferring their consciousness into a clone if required. They also always make backups of their consciousness so that it can be transferred to a new stack in an emergency. Less wealthy or poor people do not have this option. They can be transferred to other bodies if they wish. "Altered Carbon" paints a bleak picture of the future in which the gap between rich and poor is extremely wide. Through technology, an elite has separated itself from the rest and achieved a god-like status. The example shows that cyborgisation can extremise property relations. Does cyborgisation threaten to increase social inequality even more?

Social developments

Historically speaking, social inequality has been and continues to be subject to constant change. Today, ownership structures are virtually balanced compared to the Middle Ages. According to a 2016 study, the top ten per cent in Europe have an average of 37 per cent of national income (source: RP Online). In the Middle Ages, the proportion of peasants in Europe, the poorest section of the population at the time, was around 90 per cent (source: life-in-the-middle-ages.net). However, the development of new technologies has fundamentally changed our society. Thanks to industrialisation, new employment opportunities have developed for people with little or no education. One example of this is Fordist assembly line work. These people were able to carve out a slice of prosperity, albeit only a small one. In our information and service society, however, this is changing again. A high level of specialised knowledge is required. New technologies are making more and more human labour superfluous. Less or poorly educated people are the victims of this development and their living conditions are becoming more precarious. One example of this is the traditional assembly line worker, who is increasingly being replaced by machines. However, people who are dependent on flexible working conditions can also live in precarious circumstances.

In this view, changes in social inequality are triggered by the development of new technologies. Fears that cyborgisation will increase social inequality are therefore not entirely unfounded from a historical perspective. However, I would like to counter this with an argument.

Trust

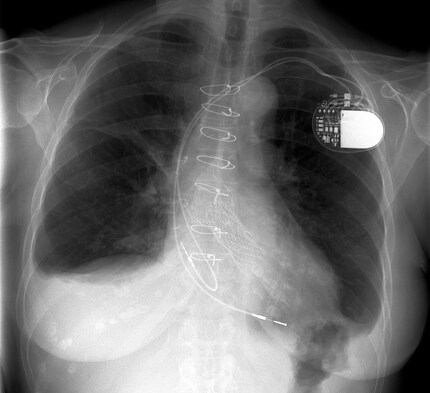

The cyborg society is a highly technologised one. Above all, this requires people to have a great deal of trust in technology. This may sound a little ridiculous using the example of a smartphone, but if we take a pacemaker as an example, things look very different. If we need a pacemaker, we have to place a great deal of trust in its functionality and efficiency. Without this trust, nobody would have a pacemaker fitted. The same applies to smartphones - it doesn't have to be a matter of life and death: If we are dependent on our mobile phone when we are out and about, we have to trust that it will not let us down. For example, when we are waiting for a life-changing call or have lost our way somewhere in the middle of nowhere. In these moments, we place enormous trust in the knowledge behind the devices. Most of us don't understand how these technologies work, or don't fully understand them. We enter into a relationship of dependency. We are dependent on the knowledge contained in the technologies. If we want to use them, we are forced to put our trust in them, so to speak. This trust that we place in knowledge and therefore in our fellow human beings means that we are very much involved in social processes.

The knowledge that goes into cyborg technologies is expert knowledge. In most cases, the knowledge of several experts is required to produce such a technology. This can be illustrated by the example of the pacemaker. In order to be able to develop a pacemaker at all, knowledge of the interaction between the heart muscle and the conduction system must exist. Then the pacemaker has to be powered somehow. This works with a lithium battery. Knowledge is also needed to develop this. Then the device itself also has to be developed. As I'm not a specialist, I'm sure I've forgotten something else. But the above shows that several knowledge systems come together to produce cyborg technology. We therefore place our trust not just in one knowledge system, but in entire knowledge systems, and we trust that they will work together. After all, not every wearer of a pacemaker has a host of experts around them at all times who could react immediately in an emergency. When we use such technologies, we trust that they have been developed and tested correctly.

Cyborgs live in constant danger

There is always a certain risk associated with the use of complex technology. The pacemaker could stop working. Using cyborg technologies is dangerous, we have to rely on others to ensure that the technologies are safe. This dependence on knowledge systems makes cyborgs highly social beings. They are not only dependent on expert knowledge, but also on other cyborgs. The boundary between the individual and society is becoming increasingly blurred. Cyborgs are aware of their dependence on knowledge systems and other cyborgs. After all, there is always something social in technology. As cyborgs, we take risks and give up part of our individuality.

The social as an opportunity

In this dependency, or rather the increasing importance of the social through cyborgisation, I see the opportunity that the future doesn't have to be as bleak as in "Altered Carbon". As we optimise our bodies, we also become more vulnerable. The more optimised we are, the more vulnerable we are. Optimisation therefore not only gives us advantages, but also disadvantages, as we give up part of our individuality and become dependent. This dependency turns us into even more social beings. Cyborgs cannot afford to live in castles in the air - both figuratively and literally - like the elite in "Altered Carbon". They have to be social beings if they want to survive. As has been the case since time immemorial. I am not suggesting that we will no longer have differences in a cyborg society. Social inequality will probably always exist. But I still don't see conditions like those in "Altered Carbon" in a cyborg society.

What do you think? Will the cyborg society be a utopia or a dystopia? Or do you see it like me and tend towards neither?

From big data to big brother, Cyborgs to Sci-Fi. All aspects of technology and society fascinate me.

From the latest iPhone to the return of 80s fashion. The editorial team will help you make sense of it all.

Show all