Guide

This is how you make iPhones child-friendly

by Florian Bodoky

A draft of the COVID certificate is here. And it raises questions. But you already have a less complicated and less error-prone solution at home.

Two pricks, and you’re vaccinated against COVID: the risk of infecting someone or becoming infected yourself is drastically reduced. Theoretically, you would then be exempt from the obligation to wear masks, which is currently still in force, but might or should soon be lifted. The federal government is staying tight-lipped on this.

Here’s the problem: vaccination is invisible. How can you distinguish a vaccinated person from one who simply says they’re vaccinated?

What’s needed is a certificate. The federal government has presented its solution. It should be available to the general public by the end of June. The news portal Watson has analysed the solution, and the developers at Ubique have published the code and principles behind the app on GitHub.

Once the government rolls out the certificate, here’s how COVID checks will work:

Here’s the problem: a security solution is only as strong as its weakest link. Most people employed at entrances to various attractions in Switzerland are not trained in performing identity checks. This is a glaring hole in the solution. In jargon, this is called «weak verification». And even if the employees are trained, their error rate is still higher than that of a machine.

As the solution stands, the federal government is issuing a state-of-the-art certificate. The certificate is not the problem. The problem is the identity check being performed by the lifeguard’s cousin. And this despite the fact smartphones have built-in tools for automated biometric verification.

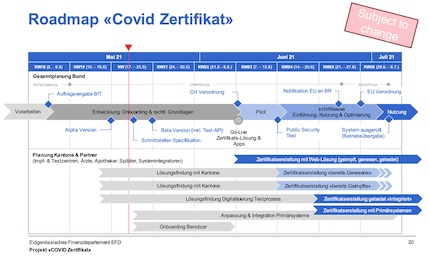

A look at the app’s background and the entire system reveals why this is all so complicated. Perhaps – the diagram explaining what happens where and how is full of spelling errors, made-up words and undocumented features. The diagram is barely understandable.

Long story short, there must be a better solution out there.

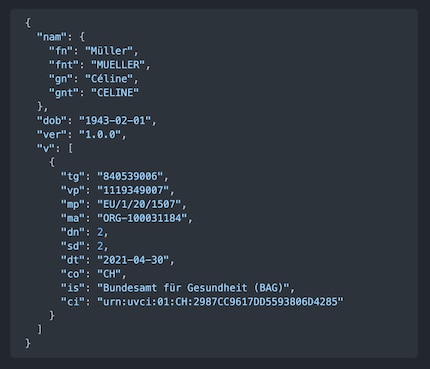

The Covid certificate stores the following data:

The last set of data is stored redundantly. The entries under «tg», «vp», «mp» and «ma» all store the same information about the same vaccine and disease, just in a different format.

The so-called COVID certificate essentially answers one question: is this person vaccinated? Yes. If you own a COVID certificate, you’ve officially been confirmed to be vaccinated. When I mention «vaccinated people» throughout the rest of the article, I’m referring to people who have either received the complete dose of the vaccine or have had COVID and recovered from it.

To be suitable for daily use, a certificate must be:

Then there’s the issue of scalability. According to the Federal Statistical Office, there are currently 8,667,000 people living in Switzerland. In an ideal world, the majority of these people would be vaccinated within a few months, save for those too young and the people who don’t want to be vaccinated. Each and every one of these people would be entitled to a certificate. It must be issued centrally, and it can’t be administered at the cantonal level, as is currently the case. If each of these people had to go to an additional, separate counter, present proof of vaccination and then wait, it would be an administrative burden of nearly impossible proportions.

«At least 60 per cent of these people should be able to get the certificate themselves,» says Pascal Tavernier, founder of the IT consulting firm Healthwyre. His company specialises in driving the digital transformation of the healthcare sector.

Part of the solution is your smartphone. It can exchange data, take pictures and has security mechanisms built in.

The federal government is working feverishly on the certificate. After all, the summer holidays are fast approaching, and the NZZ is affirming the notion of a brewing «wrath of the people», should the certificate not be rolled out widely by the time we catch pool fever. According to the Tages-Anzeiger, a staggered rollout of the certificate is planned.

But before any smartphone can display a QR code, the adequate technology has to be found for a database with nearly 8.7 million entries. The project will be open source. The COVID certificate should be available by the end of June.

«The technological solution already exists in Switzerland,» says Pascal Tavernier. According to Pascal, the solution has, in fact, been in use for more than 10 years, is internationally recognised and is available at no additional cost.

Pascal Tavernier believes that the biometric passport is the solution to the problem of verifying your identity. Because should you not have a smartphone with an NFC chip, then that elegant little book comes in handy.

The biometric passport, also known as the e-passport or Pass 10, has been in use since 1 March 2010. From that day forth, no passports without a chip have been issued. Passports have a validity of 10 years. So, as of 1 March 2020, all Swiss passports in circulation must be biometric.

Your passport contains data that’s officially recognised and allows you to be identified unambiguously and without doubt.

This is where things get exciting, because the biometric passport can be used to authorise a digital database via a chain of trust. The following question arises: which pool is already equipped with a biometric scanner, like those at the airport? The answer: none, they don’t have to be. A smartphone is enough. After all, if a phone’s biometric systems are good enough for e-banking, they’re certainly good enough for the pool.

This works great if you carry around a passport, but doesn’t work in the case of the Swiss ID card. It’s set to remain non-biometric for now.

You can read the data from your passport yourself, because the underlying technology of your passport is the same as for Apple Pay or Google Pay. Namely, NFC.

Because the data is internationally standardised, it doesn’t matter which nation issued the passport. All you need is an app that supports the ICAO biometric standards. For example, the app ReadID (Apple iOS, Android).

To use the app, you must first prove that you have physical access to the data on the passport: you must be able to take a picture of the passport page containing your photo. The app then compares the photographed data with the readout data. If they match, the app shows you the data from the passport.

The passport is big, clunky, and usually tucked away in a drawer at home. The Swiss ID card isn’t biometric. On the other hand, you always have your smartphone with you. Well over 70 per cent of all smartphones are NFC-enabled, which makes the rectangular pocket companion a perfect identifier. It’s enough to cover 60 per cent or more – as Pascal’s solution aims to – of all individuals who own a COVID certificate.

Here, too, the concept of the chain of trust comes into play. Your smartphone has a pretty good, pretty sophisticated security system. Your iPhone recognises your face even in the dark, and most smartphones are equipped with fast and reliable fingerprint sensors. Both authentication factors are good enough for all e-banking apps to trust the one and/or the other.

Your fingerprint and facial data is stored locally on your phone in some sort of secure enclave. Neither Apple nor Google knows what your face or fingerprints look like.

In practice, authentication via smartphone would look like this:

This doesn’t mean biometric data should be stored centrally. Bundesbern shouldn’t have your fingerprints in stock; that would be slightly undemocratic. Pascal’s solution is to validate your passport one single time on your smartphone – this extends the chain of trust by one link.

You then no longer have to carry around your passport – its data is stored securely on your phone. The entrance checkpoint trusts your smartphone. The chain of trust would then look as follows: entrance checkpoint → smartphone with passport data → database. No data has to be transmitted, as the verification takes place on your smartphone. The additional verification step of «show me your ID» is completely omitted.

Of course, there are exceptions. Not everyone has a passport, because it’s optional. Not everyone wants a smartphone with NFC capability, and some people don’t want a smartphone at all. Pascal Tavernier has also thought of this scenario. Because like any process, his idea also takes exceptions into account. That’s exactly why it’s important to him that a large part of the population can order, install and process their COVID certificate on their own.

So for the minority who don’t have an NFC-enabled smartphone, but are COVID-proof and want to identify themselves as such, there’s the option of passport control. The database is stored centrally, meaning if you’re from the canton of Glarus, for example, you’ll have no trouble getting a paper in Geneva to go to a local football game.

Pascal’s solution seems well thought out, fast and workable, as long as legal and privacy issues are addressed up front. So why is the federal government doing something that allows for human error and makes the pool queue forever and a day long?

The certificate must be ready for rollout within a few weeks and be as scalable as possible. It must be compatible with EU databases. You want to go to the pool or to the beach in Mallorca, after all.

So, the federal government has apparently opted for a «sufficiently secure» solution that’s free for you. For now, neither exceptions nor the technological capabilities of smartphones are being considered. Instead, the solution currently relies on the cooperation and patience of the Swiss.

Security-wise, there are about three points of attack that I would and hopefully will try straight off the bat, given the motto for security seems to be «just enough security» and not «bulletproof». Based on the documents, it seems okay that someone may slip through here and there. And should the database ever become overloaded, it’s also okay. This acceptance is part of any development process. These are so-called accepted risks, and exceptions are declared as such. If the exceptions remain below a certain value, then that’s ok – for example, one in a hundred people slips through. What does this all mean? Do you not have to worry about your safety, in that case? Of course you do, especially when the solution relies on people’s honesty and integrity.

Most importantly, the COVID certificate in its current form is not necessarily the be-all and end-all. Remember the Migros employees who initially counted people at the entrance and exit of each store? They’ve since been replaced by an automatic light system.

So wallet integration and biometrics may yet come. The federal government may simply not have had time to implement this solution on acceptable terms.

Journalist. Author. Hacker. A storyteller searching for boundaries, secrets and taboos – putting the world to paper. Not because I can but because I can’t not.

Practical solutions for everyday problems with technology, household hacks and much more.

Show all