Technology refuseniks: Hopeless romantics or smart sceptics?

History tells us: New technologies are either naively hailed and overestimated or demonised. More balanced opinions are generally only voiced later on. Maybe we can learn something from this for the future?

For 25 years, cars were illegal in the canton of Grisons. The ban did not just apply to special roads running through the national park or in the old town of Chur but everywhere. Between 1900 and 1925, cars were not allowed to be driven in Grisons.

In the mid-eighties, circles associated with the left-wing weekly newspaper «WoZ» were involved in heated debates about whether or not to use computers. The WoZ never introduced a ban. But looking at the following arguments (in German), some of the rhetorical grenades included quotes such as «computer technology’s inherently violent character». In addition, the editorial team had to deal with the so-called «action group against computer domination».

These are just two examples from Switzerland of hostile reactions towards new technologies. From today’s perspective, they seem extreme. It would be easy to make fun of them. But who’s to say that our present view is right? Perhaps people will make fun of us in 20 years’ time regarding our issues with data collection. They might even shake their heads in disbelief that we just accepted this. Common opinions may seem grotesque, naive or even fundamentalist 20 years down the line. There’s no way of knowing.

Things were better in the old days. Particularly the future.

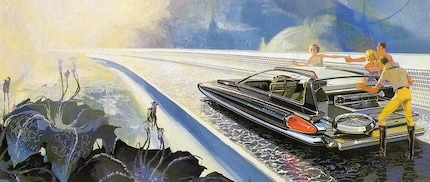

And then there’s the opposite: Over-the-top optimism regarding the future. The dominating attitude has a lot to do with the zeitgeist of the era. In the 60s, most people were convinced that technical progress would make the world a better place in a very short time. More prosperity, more equality, more fun, less illnesses. And there was reason enough for all this optimism. Inventions including the pill were the stepping stone for women’s emancipation and other social progress. Space travel, and the moon landing in particular, evoked utopian fantasies such as flying cars and family homes on mars. The flipside of progress, such as the destruction of the environment, were either still unknown or drowned out by the general euphoria.

Check out this Reddit subpage on RetroFuturism. It’s hilarious to see how people used to picture the future.

Sure, the pictures posted on Reddit could also be fake: Images created today but made to look old. Like these ads that are obviously parodies:

From the 90s onwards, the naive faith in progress was particularly strong on the stock market. Albeit, some companies did not solely rely on investors’ good faith but helped things along with a series of tricks, such as Comroad. After the Dot-Com bubble burst, things continued in the same style with biotech. In 2003, 19-year old Elizabeth Holmes founded the company Theranos, which developed a new method for analysing blood. Or rather gave the impression that this is what they did. In 2013, Theranos had a market value of nine billion dollars. Today, the company is close to bankruptcy.

Beware of common «pieces of wisdom»

New technologies will trigger worry and fear in some and euphoria in others. Obviously, both sides will be convinced that their reaction is the truth. From a refusenik’s persepective, enthusiasts are naive and negligent. From an enthusiast’s perspective, refuseniks are backward, uninspired or downright fundamentalist.

In any case, only time can tell which side was right. In hindsight, mostly both are. But is there a way of dealing with new things in a healthy way? Maybe a basic attitude to prevent us from judging things wrongly?

It would be a bit too easy to say something down the line of «new technologies are great but not everyone gets it». Take cars for example. You can’t just brand them as «great». Cars kill people, destroy landscapes, are loud and contribute to climate change. Computers aren’t only for the better either. After all, why is everybody so stressed if computers are supposed to make everything more efficient and faster?

Another thing I hear a lot is that new technologies simply expand possibilities – for better and for worse. In other words, they are neither pure evil nor perfect but neutral. An example for this would be nuclear technology. It can be used to make atom bombs or to produce energy.

In my opinion, this way of looking at things is oversimplified. After all, nuclear technology has serious disadvantages when used for generating energy and the negative outweighs the positive. And then there are achievements, such as water pipe systems, that are clearly positive. Running water was never a controversial innovation. Presumably not even ultra-conservative groups were against it.

A matter of power: Who profits from new inventions?

New technologies create possibilities – but not for everyone. Certain groups will profit more than others. An important question to raise is whom the innovation is for. That was the main issue in the computer discussion of the WoZ. Some regarded computers primarily as an instrument by means of which those in power could exercise even more power. Then there was the issue of surveillance, the resulting monopolies of certain companies and the cementing of labour division.

These points of contention are surprisingly topical as Google and Facebook prove today. However, it is unrealistic to think that a boycott would stop this development.

In the early 20th century, cars were only serving a small, wealthy minority. The car ban in Grisons was democratically legitimised through several popular votes. The first vote resulted in an impressive 84 per cent in favour of the ban. It was followed by a vote in 1925 that was relatively close. The supporters probably won because of growing tourism.

The Internet: diversity and monopolies

The Internet caused huge power shifts and is still doing so. While some of the shifts have been towards more justice and equality, others have gone the direct opposite way. One example is the Internet, where (almost) everybody is free to publish things. Media diversity is on the rise, giving underdogs a voice. By contrast, the worldwide focus is on just a handful of platforms. The number of profitable media companies is declining.

The Internet has a strong tendency to form quasi-monopolies. Take instant messengers, for example. Naturally, everybody uses the one everybody else is using. Therefore, most people will go for Whatsapp even if there are better alternatives. The same logic applies to social media: The more members a platform has, the more attractive it is and the more new members sign up. Here’s another example: If I want to advertise something, I’ll do it where I’ll reach the most people, i.e. on Google or Facebook.

As a user, quasi-monopolies are quite handy. It helps you find the deal that’s right for you without having to check several sites. However, the problem is the concentration of power that can be abused by the respective company (or state).

This is where open standards can help. Everybody uses e-mails and SMS, but these services are not exclusive to one company. In theory, instant messengers could also use a standard protocol. Social networks could be organised like a collective that belongs to its respective members. As the value of these kinds of platforms is mainly generated by user contributions, the idea is not far-fetched. However, putting it into practice is not quite as straight-forward.

Innovation is not coincidental

Technical advancements do not appear out of nowhere. Of course, there is often an element of coincidence when a scientist makes an important discovery. After all, innovations are often a matter of chance. However, if we’re talking about turning a discovery into a tangible application and introducing it onto the market – and that’s what I mean by «innovation» – this will hardly be left to chance. The only ideas that are realised are those that are expected to generate money, can be used for military purposes or will strengthen the power of a company. Innovation steers the world in a specific direction.

Something that springs to mind is the tendency to process everything via the Cloud. Although it’s undoubtedly very convenient and useful in many cases, it is also evident that we are practically being forced to do so. By no means do I always find the Cloud the handiest or safest way to do things. Technically, it would be easy to synchronise data locally between smartphones, PCs and other devices. It would be easy for Apple, Google or Microsoft to develop a solution that would make everything safe and automised. But for the time being, the fastest way between smartphone and PC is still via the Internet – even if there are only a few centimetres between the devices. This is the case not because users want it that way but because the providers do.

In Silicon Valley, mainly the disruptive ideas developed by start-ups are pushed. Disruption is less about technical advancements and more about revolution: A traditional market with thousands of companies and millions of jobs is targeted and replaced by a single company. Instead of thousands of CD shops, we now have the iTunes store. Instead of thousands of taxi companies, we now have Uber. Instead of thousands of hotels and hotel chains, we now have Airbnb.

You don’t have to be backward or technologically clueless to find this problematic. «It’s their own fault. They should have gone with the times», is a common criticism. But if you follow this logic, owners of village shops have themselves to blame for not offering the same range as Coop or Migros.

Refusal as a business model

If you’re the only refusenik far and wide, you can capitalise on it. Or at least try. A good example of this is the story about «radiation-free» Soubey.

Soubey is a remote village located in the canton of Jura. The few inhabitants of the village went a long time without a mobile phone antenna. Progress staid well clear of Soubey.

Back in 2009, the former mayor made a virtue of necessity. His vision was to turn the village into a oasis free from mobile phone radiation and tap into a tourism niche. Altough measurements showed radiation levels that were close to perfect, his project failed due to the resistance from the locals. They were more in favour of using their mobiles than being overrun by hordes of radiation allergy sufferers. Even though things didn’t go to plan in Soubey, many provincial regions succeed in attracting tourists because of their «backwardness». However, they need to watch out that the idyll is not destroyed by the tourism.

Large towns also have pockets of technology refusal that can potentially generate money. If advancement or disruption shrinks a market, the large providers are either bankrupt or busy elsewhere. But the market doesn’t disappear completely and becomes interesting for small niche providers. Record shops or photo shops specialised in analogue photography, barbers, shoemakers or elaborately designed magazines that only exist in a print version – there’s still a market for that. But it’s a lot smaller than it used to be.

Politics can’t be factored out

You can’t decide for yourself if you want a new technology or not. If the WoZ had decided against computers back in the day, it would have had zero impact on the general development of computers, but a massive one on the newspaper. Today, most of us have smartphones and use Internet services that we’re not necessarily big fans of. The reality is that by refusing them, we would only damage ourselves.

If you disagree with something, you’ve got to find other ways than hermit-like refusal. All human beings should ask themselves which kind of progress they are happy with (and with which they are not). It’s a political debate. Tech companies occasionally deny this because they don’t want anybody to interfere with their business. But even the statement «don’t interfere» is political. This is proved by the fact that Google invested 18 million dollars on lobbying in the US – more than any other company before. Landing on the moon was primarily a political act. The Russians were leading in space travel and the US were not about to put up with it. After all, they had to prove that the West’s political system was better. This power struggle cost an inflation-adjusted 120 billion dollars in total.

Opinions of so-called laypersons can be just as valuable as those of experts in the field. You don’t have to know every last detail about Android in order to think about the effect smartphones have on society. You don’t have to be a front-end engineer to have a qualified opinion on Facebook. Especially when it comes to Facebook, the following questions are valid: Whose area of expertise is this anyway? Aren’t the truly important issues matters for sociologists or economists rather than IT specialists?

Partial rehabilitation: Refusal is not stupid per se

The equation «tech refusenik = idiot» is not valid. It’s not as simple as that. In discussions about technology, it’s not about who knows the most about the topic. Fundamental scepticism, even when uttered by laypersons, can be justified. In any case, there’s no objective truth in this matter. After all, new technologies generally only bring advantages for certain groups – and disadvantages for others. Yes, it is true that progress cannot be stopped. But it can be delayed and restricted, which can be a wise tactical move.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all