Background information

Interstellar to return to the silver screen in IMAX theatres

by Luca Fontana

Are people of second generation who do military service in Switzerland «true» Swiss? That’s exactly what writer and director Luka Popadić wants to find out in his film. Yet he himself is a secondo – second generation – and a Swiss officer. Let’s get into it.

«Black coffee,» says Luka Popadić with a sigh of relief as he finally gets his steaming paper cup at Deli 1993 restaurant bar in Zurich. «I simply can’t function without coffee,» he adds.

It’s a Friday morning – not that early. Before taking his seat in the restaurant, Luka’s wearing a smart black coat and woolly hat, as well as sporting glasses and a beard. It’s cold outside. As soon as he sips the black golden substance, his gaze sharpens, and his voice certainly does. As well as being a Serbian-educated author and director, Luka is also an officer in the Swiss military.

This is exactly what he wanted to make a film about – the Swiss militia system. But it turned out completely differently. It morphed into a film that asks a lot more personal questions. For instance, whether secondos – in other words, those born in Switzerland to immigrant parents – are «real Swiss».

Luka Popadić was born in Switzerland. In 1980, to be precise. And when he talks about his wild youth in Baden in his Limat Valley Swiss German, his local patriotism couldn’t be clearer. Then, in 2009, he returned to his parents’ homeland of Serbia, where he completed his master’s in film directing at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade five years later.

«The course wasn’t easy,» Luka points out, «everything was very traditional, very strict. It’s where the country’s old directing masters lectured and passed down their teaching and wisdom, including ‘write your own films’. So I was trained as an author at the same time.» Luka leans back in his chair and sips his coffee. His gaze wanders into the distance. Or is it into the past? «One lesson in particular stayed with me: where there’s fear, there’s also an expanse.»

Luka doesn’t remember exactly who said it, but we know what it means. Essentially that the best stories are often where nobody dares look. For instance, if the story gets too close to home. People who manage to overcome their aversion to this end up finding the the best possible version of their story – and therefore the open expanse of possibilities. This was a lesson that Luka benefited from during his work on My Swiss Army, as this film originally looked completely different.

«But you’re a director! In Serbia! Why do you have to join the military? In Switzerland of all places?»

Luka begins to tell me about the origins of his latest film, saying things must have been set in motion in 2014. At that time, he’d already made several short films and presented them at film festivals around the world. Then came the moment when he had to be excused from an upcoming film festival in Serbia. Luka remembers it as though it was yesterday:

«Sorry, I won’t be there next time. Unfortunately, I have to spend a few weeks in the military.»

«Sorry, what? Did you just say the military?»

«Yep.»

«You mean here in Serbia?»

«No, no. In Switzerland.»

«Switzerland!? But you’re a director! In Serbia! Why do you have to join the military? In Switzerland of all places?»

«Well, I’m also an officer in the Swiss military.»

«An officer? But how can you be an officer when you’re already a director? That’s crazy. You can’t be both, can you?»

There aren’t a lot of countries that have a good understanding of the militia system. And even fewer where it’s such an integral part of the country’s identity the way it is in Switzerland. Nobody here questions the fact that you can be a farmer, baker or banker and still have to get your rifle out of the basement once a year to defend your country. «Having such a high rank without being a professional member of the military and instead doing a completely different job for most of the year is normal for me. But people in Serbia can’t wrap their head around it.»

And that’s how the idea for his first feature-length film based on the Swiss militia system was born.

However, Luka soon realised that while the Swiss military was a topic that’d make for an exciting report, it didn’t provide enough gravitas for a film he could take to the big screen. It needed more. More depth. More narrative.

«Then I thought of something else,» he explains. It occurred to him that his Serbian colleagues were also fascinated by the idea of a «Serb» doing military service in Switzerland despite still working and living in Serbia at the time. Why was that? What makes a second generation person do that?

«Most of all, how do the «real» Swiss in the armed forces perceive me?"

Luka wants to delve deeper into the topic and explore the fear of finding out the answer. Is Switzerland more than just a host country for him and other secondos? And above all, how do the «real» Swiss in the armed forces perceive him?

«Where there’s fear, there’s an expanse.»

All this time, Luka hadn’t stopped sipping his cream coffee. He now put his paper cup down on the table for the first time. It’s empty. «During my next stint in the military, I got in touch with the Swiss Armed Forces press office. I told them about myself, my previous work and the idea I had.» Luka leans forward, takes a quick look at the paper cup and makes sure it’s actually empty. Then he leans back again.

It took weeks for the military to respond. «They work on Bern time,» Luka jokes. But he did eventually get the green light. And not just from anyone. Directly from the federal government, from the head of the department no less. Smiles all round. «I was flummoxed.»

Luka didn’t take it for granted that the army would agree to a documentary. For one thing, the topic is often polemic. In 2015, for instance, the then Defence Minister Ueli Maurer questioned the loyalty of secondos in the army (site in German). This is why Luka planned to film and audio record the «sacred» barracks, tank hangars and firing ranges to show an unfiltered view of the army and its members. This included all their absurd moments from suffering to misery and everything in between. Despite it all, this borders on slapstick. Anyone who’s done military service will know that. But what about the others?

«I never gave the Swiss army permission to veto my creative work. I wanted to be independent. This was something that was important to me.»

However, as a letter from the head of the army notes, they were keen to establish a «dialogue» with the Swiss people – and Luka rightly gives the military leadership credit for this. This may have been classic miliary jargon, but it was sincere. For Luka, this was both euphoric and scary at the same time. Ultimately, the army was placing a lot of trust in him.

«The Swiss army never had permission to veto my creative work. I wanted to be independent. This was something that was important to me. Without that caveat, I simply wouldn’t have made the film, and the army respected this,» explains Luka. In return, he assured the military he’d always be open and transparent about the status of the project. Meanwhile, the army was confident that Luka wouldn’t do them dirty.

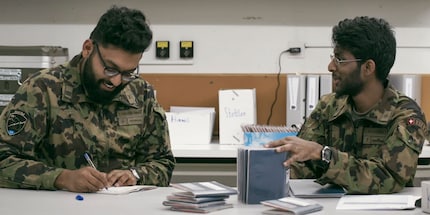

The next part of the process was where Luca had to choose three protagonists: Saâd, Thuruban and Andrija, three Swiss officers with Serbian, Sri Lankan and Tunisian roots. As he does with the army, Luka also has a great responsibility towards them as they show their most personal side. However, he did give them a right to veto. Right from the start, Luka knew he was going to do this. «I didn’t want them to say things that they wouldn’t feel comfortable with later or that could potentially ruin their professional life – I wanted them to have a say."

«The film was good, but not good enough. It felt like something was still missing. Or rather, someone was missing – me.»

However, none of the film’s three protagonists used their right to veto, which makes Luka quite proud. For him, this meant he’d prepared his questions well and asked them fairly, in the context of the film, at least. For instance, if they’d be prepared to give their lives for Switzerland should there ever be a war. Heavy stuff.

But there was one character missing.

«You’re right. I resisted being in the film myself for a long time. I don’t like being the centre of attention. I prefer to leave that to others,» says Captain Popadić of all people, sitting casually in his chair. If he feels uncomfortable admitting it, he doesn’t let on. Luka could definitely have been an actor as well as an author and director.

In fact, his reluctance was probably one of the reasons the production of «My Swiss Army» took eight years. It was partly because the pandemic slowed things down in 2020. But Luka had actually already finished the film in 2021, including editing, sound and even subtitles. However: «The film was good, but not good enough. It felt like something was still missing. Or rather, someone – me.»

That’s it. The fear that blocked his expansive view.

Luka made a difficult decision.

«I gave up on the first cut,» sighs Luka, «it was just impossible to thematise my own story and weave it into the current cut. It wouldn’t have fitted. We really had to start from scratch again.»

Luka would’ve liked to work with the then editor Stefan Kälin again. However, conflicts with his schedule made it impossible. Maybe it was better that way. In any case, getting a fresh look at over 140 hours of footage and re-editing it would’ve been difficult. So Katharina Bhend stepped in. She made it clear from the start that she’d only edit the film if the director was also in front of the lens as the fourth protagonist and narrator.

Fast-forward three years and My Swiss Army has been released in over 30 German-speaking cinemas. At the start of the year, it even won the audience award at the Solothurn Film Festival (page in German). This was a big thing for Luka. Especially after getting through eight years of production and resistance that sometimes came from unexpected places.

«If the left supported the film, it’d probably indirectly mean supporting the military.»

«Even financing the film didn’t go smoothly. Secondos in the military is still an uncomfortable topic for some.» Luka sees himself as politically neutral. However, he received more support from the political right. «Crazy, isn’t it?"» he says with a mischievous grin. But when he thought about it, he realised why.

«For the left, supporting the film means indirectly supporting the military,» explains Luka a little more seriously as he leans forward and notices that his cup of black coffee is still empty. «At the same time, they couldn’t actively speak out against the film because that’d also be against secondos – a political no-go. So they were stuck in limbo where no reaction was also a reaction, but the least bad of the options.»

The quiet disappointment of this man from Baden with Serbian roots is palpable. After all, his film is intended to be more than «just» about secondos in the military or about sending a certain message. Rather, everyone should be allowed to decide for themselves what they like about the film. «I just want to show how complex and multifaceted Switzerland is. And if the film ends up helping us all feel a little more connected, then I’ll be happy.»

Luka’s gaze wanders back to the paper cup. He finally grabs it and stands up. «Right, now I need another black coffee.»

My Swiss Army has been showing in over 30 German-speaking cinemas since 4 April, including those in Baden. The documentary will be released in French-speaking Switzerland at the beginning of September 2024.

I write about technology as if it were cinema, and about films as if they were real life. Between bits and blockbusters, I’m after stories that move people, not just generate clicks. And yes – sometimes I listen to film scores louder than I probably should.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all