Opinion

The Mark Zuckerberg dystopia

by Oliver Herren

Facebook has extended fact-checking to Instagram. We've already seen some surprising photo blocking, but that's just the tip of the iceberg. The idea itself is highly problematic.

A little oddball has been in the news recently. Facebook introduced a fact-checking mechanism on Instagram as it had previously done on its own platform. Unsurprisingly, the fact-checking has, in some cases, failed utterly ridiculously.

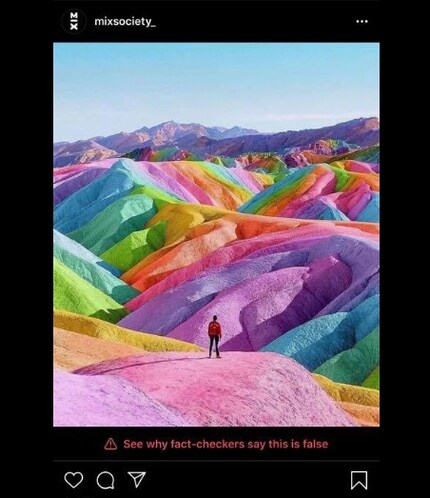

We could, for example, cite the times when this incredible verification informs us that certain photos are "fake".

Obviously, these mountains don't look like this in real life. But, on the other hand, nobody pretends they do. Everyone understands that this is an imaginary landscape. But is this a good reason to ban the image from the platform? Would creativity now be forbidden?

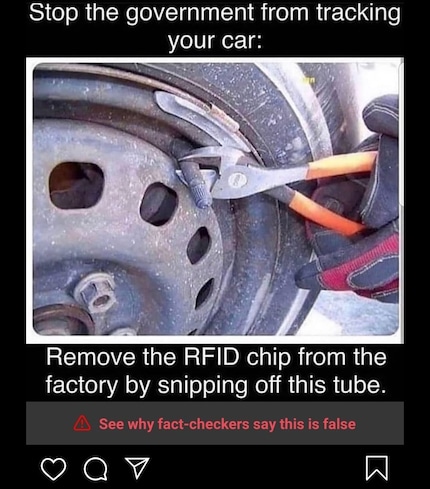

What about this fact-check informing me that I can't get rid of a possible RFID chip by cutting the valve on my car tyres? Thanks very much, I'd already got my hedge trimmer ready.

The verification mechanism allows users to flag up images themselves. These are then verified by a third-party company. In principle, this feature doesn't seem so bad, given that it's human beings who are examining the images and they aren't being filtered by vulgar algorithms.

However, our fellow human beings are not infallible, especially when their work has to cost as little as possible. They are then under extreme pressure, having to assess each image in just a few seconds and all day long. I suppose the staff assigned to this task have to be as cheap as possible, so some employees must lack the general culture that is sometimes necessary. In particular, we're talking about Facebook moderators working from the Philippines. These employees could consider the famous Vietnam War photo of a naked nine-year-old girl as child pornography content and censor it. Incidentally, Facebook has effectively blocked this photo, and the only plausible explanation here remains ignorance.

Even if trained people had the time to make these decisions, some of them could still be challenged. After all, an image in itself is neither good nor bad; it all depends on the context. Social networking platforms mix the most distant sources and the most varied contexts in the same news feed. So you lose sight of the original situation and everything is decontextualised. These are not ideal conditions.

Satire, for example, is a very special context. From a purely factual point of view, satire is nothing more than disinformation. That said, its raison d'être goes far beyond the facts. It's about caricaturing a certain situation so that everyone can appreciate how ridiculous it is. Unfortunately, reality is sometimes so ridiculous and so grotesque that it's not much different from satire in the absence of context.

When it comes to Instagram, another element is also of particular importance: art. When it comes to painting, it's perfectly acceptable to depict things that don't reflect reality. When it comes to photography, which can also be a form of art, the idea often prevails that images must above all be a form of documentation of the real world and that anything different is therefore a pack of lies. This inflexible and outdated view of things doesn't really suit Instagram, given that the very platform made its name thanks to the artistic effects offered by filters.

Digital art often looks realistic. So only the context can determine whether an image represents reality or an imaginary world. Should a photo be purely artistic, purely realistic or can it be a bit of both? Only the answer to this question allows images to be assessed fairly.

In the case of news and features, I expect photos not to be distorted, otherwise I feel I am being misled. This is particularly the case with photos that appear in Geo magazine or National Geographic. The displeasure over the retouched photo of some of the world's oldest trees at night is justified. It is undoubtedly a pretty picture, but its publication in National Geographic suggests that it is a documentary image. This publication has therefore been removed.

To put it simply, let's imagine that the employees who check the news only check content for documentary purposes. Here they would have no financial incentive as it is much simpler to point out the inaccuracy of idiotic memes than publications intended to be informative. Let's imagine a world in which this system could work.

Fact checking itself would remain problematic.

Who are the employees responsible for checking this information? Are they any better than the internal auditors at Spiegel, the New York Times or the Guardian? I very much doubt it. What right does Facebook have to allow itself to rule on the subject? Who can really verify the information reported by war reporters? Who can claim to know whether they truly have a global vision or whether, on the contrary, their perspective is limited?

Certainly not an army of poorly paid employees who check the information contained in millions of publications every day.

And if there were a centralised body deciding what was good and what wasn't, wouldn't we be sinking into the world of 1984? Because of their monopoly position, groups such as Facebook or Alphabet have relatively extreme powers of definition. They can simply make certain publications disappear. If this power is not used responsibly, in the worst case we see the emergence of a kind of Ministry of Truth, like in Orson Wells' 1984. Anonymous and inaccessible employees decide what content will or will not be visible based on obscure criteria.

As if this situation wasn't already problematic enough, let's not forget that a psychological mechanism is also at work among people checking the news: we often don't believe what is plausible, but rather what we want to believe. This means that a large number of people stick to their positions even if it is possible to refute each of their arguments. Those responsible for verifying information prefer to ignore the evidence that fact-checking does not fulfil its purpose.

What about the poor teenage girls who choose a model who is perfect from every angle as their model and compare themselves to it until they're sick of it, even though the photos posted on Instagram don't match reality at all? Couldn't Instagram help them by adding prevention mentions?

Once again, I remain sceptical. Indeed, this solution would not solve the underlying problem. There are models who look completely unreal in real life. In other fields too, there are a multitude of unattainable models, whether real or fake. Learning to live with them is part of the transition to adulthood. It is neither possible, nor desirable, to censor all publications that risk destabilising teenagers. On the contrary, we should be seeking to create an environment in which everyone feels they are recognised for their true worth, regardless of their performance or appearance.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

This is a subjective opinion of the editorial team. It doesn't necessarily reflect the position of the company.

Show all